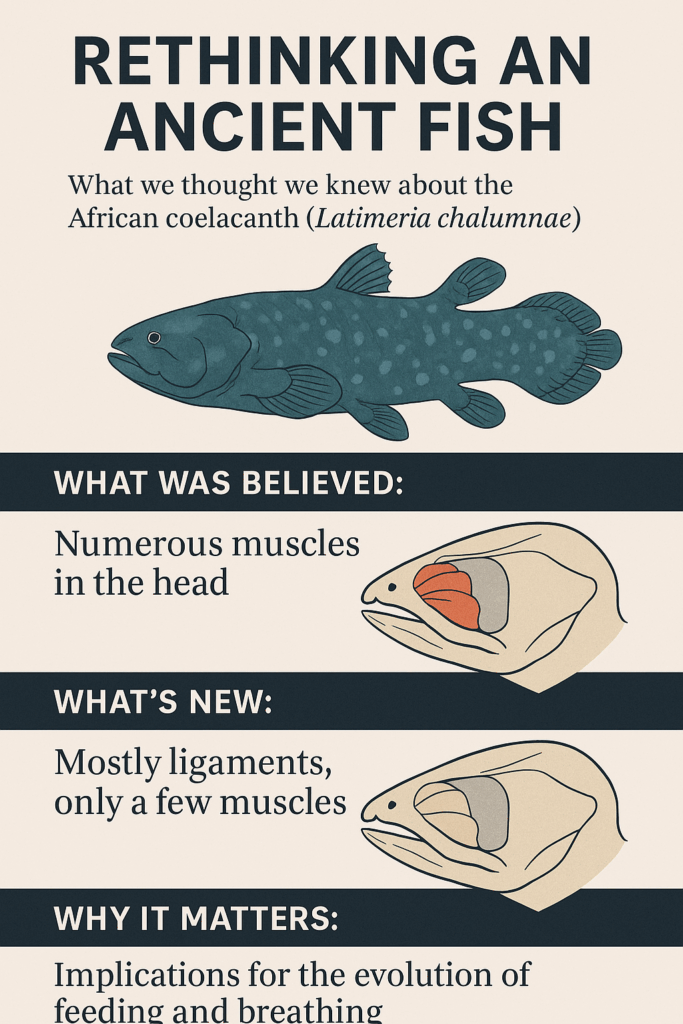

For decades, the African coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) has been hailed as a “living fossil,” a rare window into the deep evolutionary past of vertebrates. With its fleshy, lobed fins and ancient lineage, it was believed to offer clues about the transition from aquatic to terrestrial life. But a recent study has shaken up what we thought we knew—revealing that even this evolutionary icon has been misunderstood.

What We Thought We Knew

Coelacanths were long thought to possess a complex array of cranial muscles that helped them feed through suction, similar to early jawed vertebrates. Anatomical diagrams dating back to the 20th century described a head full of intricate muscles—seemingly supporting the idea that the blueprint for modern feeding and breathing systems was already present in these ancient fish.

But here’s the twist: almost all of those “muscles” weren’t muscles at all.

What the New Study Found

Using detailed dissections and high-resolution digital scans of Latimeria specimens preserved in museum collections, a team of researchers led by Sam Giles (University of Birmingham) and colleagues discovered something startling: up to 87% of the previously described cranial muscles were actually ligaments or connective tissues. Only a small fraction of the structures identified in earlier studies could actually contract and function as true muscles.

Even more surprising was the realization that this mistake had persisted for decades—largely because opportunities to study coelacanths are vanishingly rare. These fish live at great depths, and preserved specimens are few and precious. The study, published in Science Advances, relied on some of the only available preserved coelacanths, dissected with surgical precision and paired with digital modeling to minimize damage.

Why It Matters: Rethinking Suction Feeding and Air Breathing

These findings do more than correct an anatomical error—they challenge key assumptions about the early evolution of vertebrate feeding and respiration.

Coelacanths were thought to employ suction feeding powered by a suite of cranial muscles, suggesting that these mechanisms were already in place in early lobe-finned fishes. But the new study paints a different picture. With fewer muscles than expected, Latimeria likely lacks the capability for strong suction. This implies that the sophisticated suction feeding seen in ray-finned fishes and amphibians must have evolved later and independently.

In terms of breathing, the reduction of cranial musculature may also hint at a simpler, less specialized system for ventilating the gills or accessing surface air, further distancing coelacanths from the ancestral blueprint for terrestrial breathing.

A Lesson in Scientific Humility

This revelation is a striking reminder that scientific knowledge is always provisional—even when it concerns long-studied, “classic” species. The coelacanth, once viewed as a near-perfect proxy for ancient fish, turns out to be more derived than we assumed in crucial aspects of its anatomy.

It also underscores the importance of revisiting old assumptions with new tools. The earlier anatomical misinterpretations weren’t due to carelessness—they were the best guesses based on limited methods. But thanks to modern imaging and the careful use of rare museum specimens, we now have a much clearer view of this ancient lineage.

So, What Now?

Far from diminishing its importance, this new understanding of the coelacanth only deepens its relevance. It forces evolutionary biologists to reconsider timelines: when and how did jawed vertebrates develop complex feeding and breathing systems? What other “primitive” features in fossil or extant species might actually be misunderstood?

By stripping away centuries-old assumptions, the coelacanth is once again doing what it does best: illuminating the hidden paths of vertebrate evolution.

Key points

- Study Focus: Reanalysis of cranial muscles in Latimeria chalumnae using modern techniques.

- Main Finding: Most previously identified muscles were actually ligaments; only ~13% were true muscles.

- Implication: Challenges long-standing models of how suction feeding and air-breathing evolved in early jawed vertebrates.

- Lesson: Even iconic species can be misunderstood—until we look again, more carefully.

Suggested Reading

Datovo, A., & Johnson, G. D. (2025). Coelacanths illuminate deep-time evolution of cranial musculature in jawed vertebrates. Science Advances, 11(18), eadt1576.

Leave a comment