Lampris guttatus, commonly known as the opah or moonfish, is a large fish with small red fins and can grow up to 61.8 meters long. It belongs to the family Lampridae and genus Lampris. It has a cosmopolitan distribution and is pelagic in nature. What brings this fish into limelight is the finding of recent study[1] which makes opah, the first warm-blooded fish every discovered.

Animals can be divided into Cold blooded and warm blooded based on the ability of its body to maintain heat. In most of the animals, body heat fluctuates with the change in environmental temperature and are cold blooded or poikilothemic. Other organisms which maintains a constant body temperature in spite of the changing environmental temperatures are considered warm blooded or homoeothermic. Birds and mammals are the only true warm blooded animals.

Most of the fishes are cold blooded, meaning that they have body temperatures that match the surrounding water. Some have the ability to make specific body parts warm like tuna and sharks using the swimming muscles. But none of the known fishes have the ability to keep their entire body war, except for opah. This makes opah the first warm blooded fish ever discovered. They have the ability to keep the entire body around 5 degrees Celsius above the surrounding water. But they cannot be compared to a bird or a mammal who can maintain a constant body temperature throughout life. So this fish is considered warm blooded but not true homoeotherm.

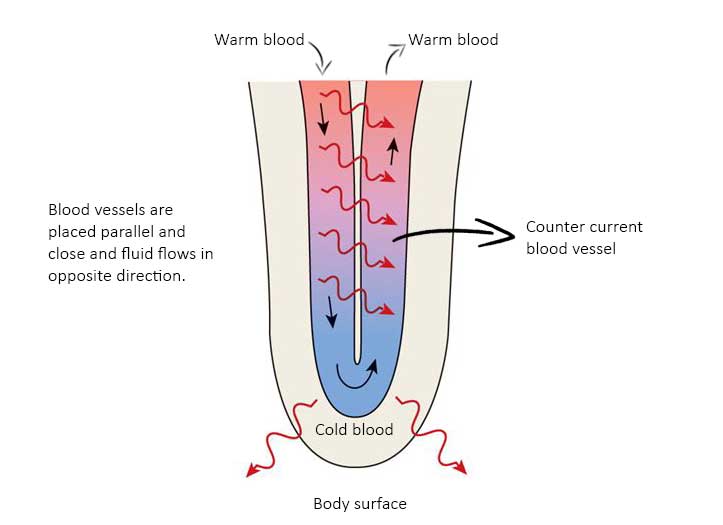

Contraction of all animal muscles can produce heat. In most of the fishes, this heat is immediately lost to the surrounding water. Most of the fishes conserve this heat with a heavy insulation or using a network of small blood vessels called retia mirabilia, which acts as a counter-current heat exchange mechanism. The body of fish may be insulated, but when the warm blood reaches the gills, where it makes close contact with the cold sea water, the heat is lost immediately. Opah is having a brilliant design here. While most of the fishes keep its retia mirabilia in muscles, opah has placed it in gills, thereby isolating them from heat loss.

Counter-current heat exchange is a mechanism in which two vessels with flow in opposite direction are placed parallel and close together. Opah continuously uses its pectoral muscles and heat is produced there. This heat is transferred to the blood vessels and towards heart. This warm blood is first pumped to gills and after oxygenation to various parts of the body. Here, arteries carrying warm blood towards gills are placed parallel to arteries carrying blood away from gills. As these vessels are placed close to each other, heat is transferred from incoming artery to outgoing artery even before it reaches the gill surface. Thus the heat produced is conserved in the body.

The authors confirmed the findings by catching live fish and releasing them in sea with implanted small thermometers. They recorded consistently higher temperatures compared to outside waters. An almost the whole body stayed warm. This ability helps opah to stay for a long time at depth without surfacing.

References

[1] Wegner N.C., Snodgrass O.E., Dewar H., Hyde J.R., Whole-body endothermy in a mesopelagic fish, the opah, Lampris guttatus, Science 2015, 348, 786–789

1 Comment