A vertebrate with one of the longest necks

When paleontologists uncovered the fossils of Dinocephalosaurus orientalis in the Middle Triassic rocks of Guizhou, China, they were confronted with one of the strangest body plans in reptile history. This marine reptile, belonging to a group of long-necked archosauromorphs, had pushed anatomy to extremes: a neck made of over 30 vertebrae, longer than its torso and tail combined.

A neck that defies expectations

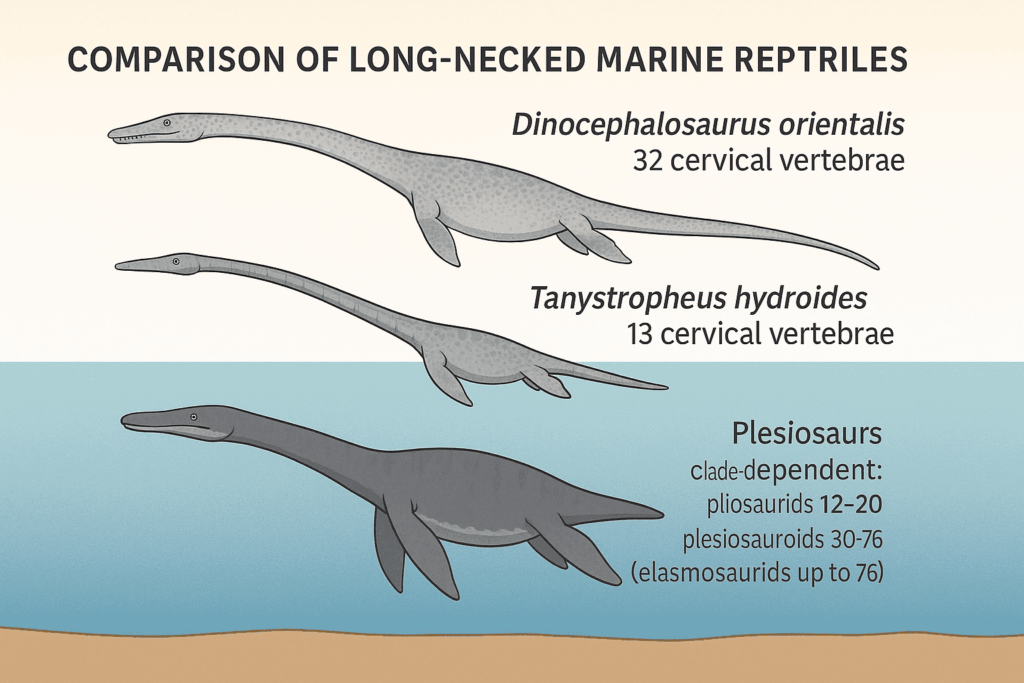

Most reptiles—even long-necked ones like plesiosaurs—show some balance between the length of their neck and body. Dinocephalosaurus, however, stretched its cervical series into something extraordinary. With 32 cervical vertebrae, each reinforced by long, overlapping cervical ribs, its neck formed a stiff yet elongated structure. This gave the animal a snake-like profile, though it was far from flexible in the way a snake is.

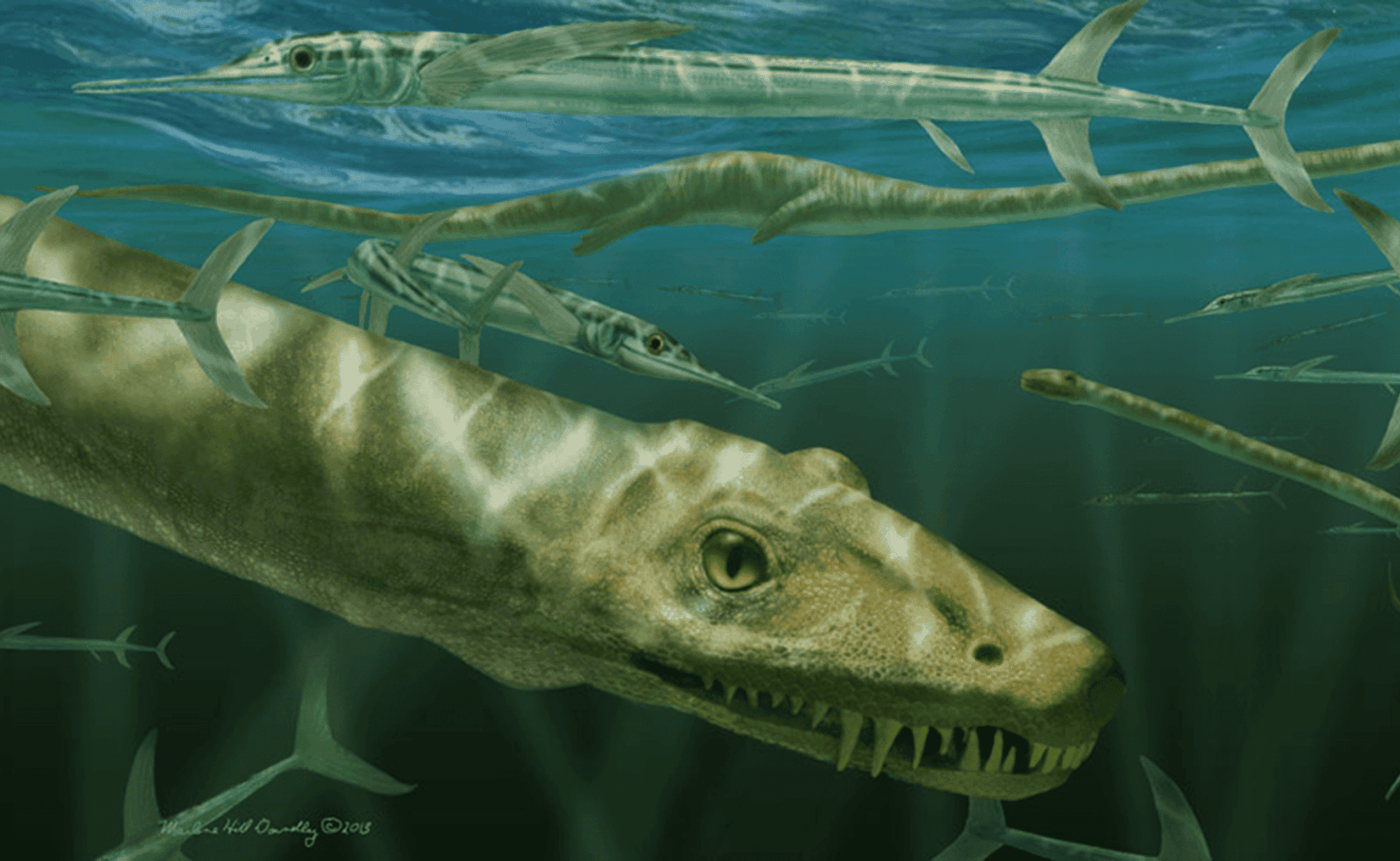

The stiffened design suggests the neck was not used for rapid twisting but may have acted as a precision strike weapon. Paleontologists propose that Dinocephalosaurus hovered motionless in the water, lunging forward with its narrow head and elongated neck to snap up fish and squid. In a murky Triassic lagoon, such a stealth-based predatory style would have been highly effective.

Life as a marine predator

The rest of its skeleton confirms it was a fully marine reptile. Paddle-like limbs show adaptation to life at sea, and the structure of its ribs and vertebrae suggests buoyancy control for an aquatic lifestyle. Remarkably, later discoveries even revealed evidence of viviparity (live birth) in this animal—a rare trait among archosauromorphs, indicating that Dinocephalosaurus may never have needed to return to land.

Together, its body paints a picture of a marine ambush predator: long neck extended into schools of fish, sudden suction-feeding strikes, and powerful limbs for maneuvering in shallow seas.

Kinship with Tanystropheus

Where does such a bizarre reptile fit on the evolutionary tree? Dinocephalosaurus is closely allied with Tanystropheus, another Triassic reptile famous for its disproportionately long neck. Both belong to a branch of early archosauromorphs sometimes grouped in Dinocephalosauridae, distinct from the direct ancestors of crocodiles, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs.

While Tanystropheus seems to have been a semi-aquatic shoreline hunter, Dinocephalosaurus was more fully adapted to the sea. Together, they highlight an evolutionary experiment with elongate necks in the aftermath of the Permian extinction, when ecosystems were being rebuilt and new niches opened.

Why the long neck?

The mystery remains: why evolve such an extreme neck? Several hypotheses have been put forward:

- Stealth hunting: A long reach allowed it to strike prey while the bulk of its body stayed hidden.

- Hydrodynamic feeding: The stiff neck may have helped generate suction, drawing prey into the mouth.

- Niche partitioning: Extreme elongation may have reduced competition with other predators.

Whatever the exact reason, Dinocephalosaurus demonstrates that evolution is willing to test the limits of anatomy in surprising ways.

A triassic oddity with lasting lessons

In the grand story of vertebrate life, Dinocephalosaurus orientalis occupies a special chapter. Neither dinosaur nor plesiosaur, it was part of an early wave of reptilian innovation. Its improbable neck reminds us that the Triassic was an age of experiments—some successful, some evolutionary dead ends, but all fascinating.

It may have disappeared more than 230 million years ago, but its fossils continue to puzzle and inspire, showing us that sometimes the strangest designs are also the most revealing.

Suggested Reading

SPIEKMAN, S. N. F., WANG, W., ZHAO, L., RIEPPEL, O., FRASER, N. C., & LI, C. (2023). Dinocephalosaurus orientalis Li, 2003: a remarkable marine archosauromorph from the Middle Triassic of southwestern China. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 114(3–4), 218–250. doi:10.1017/S175569102400001X

Leave a comment